By Evan Ash Sometimes I hesitate to watch the news...so much injury and sadness is the focus of the reports. One day I looked on the internet to see what was the news in different cities, to see if the Kansas City area was different. I found that most on-line news stories in other cities had negative and upsetting content...all but Fargo, North Dakota. That day there the headline was about the local disk jockey’s birthday! In the negative news you typically see a call for justice in the form of punishment and self-righteous reprisal. “An eye for an eye...” But as Tevye, in Fiddler on the Roof , said, “If an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, the world will be blind and toothless!” Something similar was observed by Ghandi. A fully functioning, full-bodied world needs a different answer to how we can live and find the blessings of life. There has to be another way! Have you noticed how once and awhile in those local news stories you see a victim or their family praying for the person who caused their injury and loss. And do you wonder, where did that come from? We saw this last week where I live at the memorial for a promising 14 year old boy and his grandfather, gunned down by a fanatic at the Jewish Community Center. Here the community and family focused on celebrating the life of this two loved persons. They touched a lot of lives. Even one of my colleagues worked with the teen at their church. Any talk of retribution was buried in the news in light of the more newsworthy accounts of celebration and self-care. Turn the other cheek, give more than is required, respond to the need of another person, all these when you may be faced with pain and loss. Do crazy things like love your enemy, pray for them? The great mystery is the power that comes from the paradoxes of life. Boundaries as Paradoxes Here is a simpler, nearer to home example: why do we build fences around our backyards when we have children? I am sure you can come up with several practical reasons. But do you realize the message you send to your children when you build that fence? They are free to do anything within this fence. Boundaries give us freedom and purpose! Within that fence, your children are stimulated by the boundaries to be creative... to make new worlds, to imagine places they have been or not been, to explore stories, to act out tales of adventure, and discover the wonder and fascination with an earthworm, a fallen bird’s nest, an uncovered root or hole, a flowering bush. An empty box becomes a cave or a castle, a fallen limb or branch becomes a sword or a horse, a table becomes a mountain to climb. Such results are fostered when boundaries force us to see the world in its terms not just our own, to see the world, and ultimately ourselves for what we truly are. When we do not face any limits we are not required to develop those capacities that cause us to grow into our human spirit. The human spirit is fed by the challenges limits in life place upon us. Without those limits we do not build character and inner strength. Without those limits our souls will wither and die. Compassion The boundary I invite us to appreciate is compassion. “Compassion” in Latin means “co-suffering”. It is the capacity to accept, understand, and share the struggle of another person and their situation. It means a willingness to look beyond only one’s self in situations, to include all that is taking place, including what exists beyond the confines of you and your personal awareness, to see more than your needs and fears, to make room in your view of what is also taking place in the other person. Again, it means being willing to see more than yourself. Yet, at the same time, ironically it means you will be able to see yourself more clearly as a result. The mystery of paradoxes! Marshal Rosenberg, in his book Nonviolent Communication , gives us an example of how compassion helps us see more creatively. He quotes a Jewish therapist named Elly Hillesum who survived a World War II concentration camp: “I am not easily frightened. Not because I am brave but because I know that I am dealing with human beings, and that I must try as hard as I can to understand everything that anyone ever does. And that was the import of this morning; not that a disgruntled young Gestapo officer yelled at me, but that I felt no indignation, rather real compassion, and would have liked to ask ‘Did you have a very unhappy childhood?, has your girlfriend let you down?’ Yes, he looked harassed and driven, sullen and weak. I should have liked to start treating him there and then, for I know pitiful young men like that are dangerous as soon as they are let loose on mankind.”[1] Closer to home, I can think of my own challenges to be compassionate. In my work it comes easily as it is part of my sense of my work with families, as it has been with others over the 37 years of my priesthood. But there are so many ordinary everyday examples, such as driving in traffic. A driver rushes past me on the interstate as we are driving along at 65 miles per hour, and cuts in front of me. It causes me to immediately apply the brakes. My blood pressure goes up, my eyes dilate, as a rush of adrenaline set me up for urgency. The stress generates a fear of a collision and I feel energized and agitated, all initially expressed in anger and angry words I will not repeat here! Sometimes I exercise compassion. I think: that person must be rushed by something of great concern to them. I begin to imagine different scenarios: others are counting on them, they are late to work? A child is alone somewhere waiting for a parent? Someone is ill and needs help? I also know that perhaps they are just immature and their rash actions will cost them one day...I hope the lessons are not too costly...to them and others. And I find that as my spirit is exercised, my mind and body return to normal and I can get on with my life. Again, it means being willing to see more than yourself. Yet, at the same time, ironically it means you will be able to see yourself more clearly as a result. The mystery of paradoxes! The creativity of compassion is my topic for today, And how it can be a paradoxical and productive tool for mediation. Elements of Practicing Compassion My primary work for the past 19 years has been with parents and family members. But my active role as a mediator began decades before. And I think we all long for those unexpected moments in a mediation session, especially in these intensely personal settings, when the two parties connect over a wide gulf of pain and struggle, be it an apology for a past hurt, a flash of recognition in the face of a party, or sudden tears. There is a sudden quietness that occurs that tells you this conflict has hopes of being resolved. I recall a family, divorced for several years, dad asking for more time with his children and mom denying his request in this classic scenario. Through court documents demeaning faults were highlighted And the conflict between the parents grew. In our mediation session, as mom resisted his requests and dad’s tone became more demanding, I ask mom a question: “What do you think will happen if your children could spend more time with dad?” She quickly replied, “I won’t be able to count on him! He was never there! I had to do everything because he wasn’t around.” I replied, “So you had to do everything.” She replied, “Yes and when there were problems, I had to fix them because he wasn’t there to help.” I replied, “And there were problems, sometimes big ones.” She replied, energized, “Of course, and they were sometimes hard to handle, especially by myself!” I responded, with some emphasis,“And those moments were overwhelming and sometimes frightening.” She quietly replied, “Yes, they were scary.” I quietly affirmed, “At those times you were afraid...” Unexpectedly, dad jumped in, “She’s right...I wasn’t there much. I had to provide for her and the children. I don’t have a good education so I had to take jobs I could do and keep. They didn’t pay a lot so I had to have two jobs to make ends meet. But that is what a man does – he takes care of his family. She had to take care of the kids. I wasn’t home much except to sleep.” I replied, “You had to work a lot. It was what it meant to be a good man, a good husband, a good father. You were afraid you couldn’t provide for them.” Dad replied quietly, in an awkward confessional tone, “yes...it was scary...” There was that hopeful silence between them. Then dad went on, “Now I have a better job so I only have to work one job. I have more time so I can be a better father to our children. I am just asking for a chance...” This day the parents heard each other for the first time. Both had been afraid but they did not know it. From this came a different kind of discussion and they found ways for dad to play A larger part in the children’s lives And mom got some relief so she could take care of herself. Metaphors of Compassion Consequently, as the mediator exhibits compassion toward each parent/party, it becomes part of the language of the mediation session. John Haynes was a founding pioneer of our vocation as mediators. Before he died, he was working on a book on the role of metaphors in mediation. The content can be found in a series of articles on www.mediate-com .[2] He described how people want to be heard in settings where the person has something at stake. When coming into mediation, parties are typically using language reflective of a warfare motif. Win, lose, battle, and more aggressive terms often characterize the way the conflict is approached. The legal system itself often fosters this outlook as the parties are primed by the language of courts, attorneys and motions. However, when the mediator uses a different metaphor, and the remarks made to the person express that different metaphor, the parent or party, wanting to be heard, and will unconsciously adopt the language of the mediator’s metaphor. The frame of reference during the session shifts. If the metaphor of the mediator is selected to foster recognition of the value of each parent or party, and recognition of the worth of each of their challenges, a metaphor of compassion emerges. This metaphor expresses a sense of expectation and hope for them and their situation, not diminishing the dignity and worth of each parent. I personally like the metaphor of a journey. I guess it goes back to my own personal mission statement: I am walking the road with people going through a broken moment in their lives. A metaphor of compassion brings forth a new sense for life and relationship for the parties. The problem is not across the table, in the other person. Now both can look at the problem as a challenge they share. They discover they are cohorts facing the same thing, only from different perspectives because they are different people. A more realistic appraisal of resources and opportunities is now possible. Disputes vs. Conflicts It is often helpful to define the scope of the breakdown for the parents. This can be accomplished by recognizing the difference between a dispute and a conflict. While we often see these words used interchangeably, they actually are two different phenomena. A dispute is an event of disagreement. Conflict is the condition of a relationship. The Challenge of Anger It helps to recognize why compassion does not readily come into conflict. Consider how we experience events. The following diagram gives a simple description of the typical unconscious–to-conscious process leads to our actions. Perception interprets the nature of the experience and leads to the kinds of actions we may naturally take sensation -> perception -> emotion -> body –> react ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦_________¦_______________think ¦ decide ¦ respond Hurts of the past are used to justify a divorce...to look at their “ex” with compassion challenges that justification. When a person feels threatened in some way, even if it is only the rejection of their idea of what is best in a situation, the fear it generates stirs pre-conscious energy aimed at defending one’s self. We call that emotional energyanger. Anger’s benefit is to foster distance from the threat by displaying behavior that, in turn, threatens the source of our vulnerability, which for our purposes here, is in their relationship with the parent or party. Anger is a survival emotion. But it is not revealing what is truly being experienced. anger is displayed, it has resulted from an experience of pain or fear. When a person only responds to the external emotional behavior, by being self-protective, that person is not engaging the root cause of the other person’s actions. They are not connecting, they are actually disengaging. To be willing, as a mediator, to look beyond the disruptive outbursts, harsh words, threatening facial expressions, to search for the source, the mediator is expressing compassion. Mediation invites them, encourages them, to take a chance on seeing each other in the present so they can have a future not based only on past hurts. Lessons about Compassion Several lessons about fostering a potential for compassion are revealed in the brief exchange described earlier. Most may not be new to you. You may wonder why I am even taking your time to be here? What I hope you will discover is why we learned those mediation tools in the first place. Those tools are not just practical for negotiation, they bring the promise of a larger outcome to parties when we use them. Even in the less poignant mediation sessions, the benefits of these tools are fostering a life-giving change in the parties, It may show up in the relationship sitting before you, but also elsewhere in their lives. Mission Statement Think about the messages you give parties about what they will experience in mediation with you. How will you model your practice? It starts with your own mission statement for your mediation practice. The benefits of a mission statement for mediators are a) gives a sense of personal purpose, b) provides a centering point for the mediator when she/he gets stuck, and c) it provides a marketing tool for a practice that expresses the integrity of what the mediator is offering. I require my student interns to craft their mediation practice mission statement before they finish their first case. We review it again before they solo to see how real life has tested and refined it. Temple of Hope Where does that lead? I present it in the illustration of what I call the Temple of Hope (See http://www.mediate.com/articles/ashe4.cfm). This is an illustration of the integration of the elements of mediation. Together, your mission statement and the model of the Temple of Hope lay a foundation for compassion that can be subconsciously anticipated by the parties. Reflective Listening You will notice in the case I shared That the way I listened had an impact. I was reflective and focused on the vulnerable parts of their content: the size of problems mom faced, being overwhelmed, scared, dad’s sense of personal worth and the challenges, being scared. Parents’ general tendencies in mediation were studied in Israel. The research found that mothers approach answers from the standpoint of relationships Fathers tend to approach answers from the standpoint of principles. In this case, Mom’s vulnerability was revealed in the task of responding to her children, Dad’s vulnerability was what it meant to be a good man, husband and father. Unless you are so overwhelmed with your own suffering, or so callused by life experiences, compassion is opened up when vulnerability is revealed. In hearing another’s suffering, we tend to find an inner movement in our outlook when we hear the revelation. How I reflected to mom helped her to reveal her fear. When dad heard mom confirm her fear, he was moved to his confession. I simply helped him reach the level of his fear so she could hear it. Pacing You will also notice that I paced their emotions As part of my reflection with each of them. Bob Benjamin talks about this when he talks about Guerilla Mediation. Pacing is a technique where you mirror the parent’s expression of emotion but in a way that does not aggravate the parent. With mom, I gave more emphasis to my voice when she was energized, was quiet in my tone when she was more subdued. I did the same with dad. In this way, each was able to hear themselves as I served as their emotional mirror. Did I know what each would say? no! I trusted that the way I responded to them, with my own acceptance and compassion, would hopefully help them find their way. The Brain on Questions Often stressed people are hampered in their thinking and their expressions. Those of you who have learned of the brain’s activity will understand this dynamic. Those of you who have not, know it anyway! By the way, the most popular local beer in Wales is named Brain’s. This is not what I am talking about! When we experience an event, 2 parts of the brain are stimulated - The Amygdala and the Hippocampus - Each with a different history and function. The Amygdala is from the earliest part of human evolution. It is often called the primitive or “reptilian” brain. If provokes quicker responses, giving us fight of flight reactions to stressful situations. The Hippocampus is a later evolutionary development. It connects more directly to more complex memory patterns in the other parts of the brain and stimulates more cognitive activity leading to reasoning. Responses can then be more measured to the situation. When people are stressed, these 2 parts of the brain get the message at the same time and respond in a way appropriate to their function. However, the Hippocampus takes more time, even in mille-seconds to generate a response. In mediation, how do we help the parents to do their best given these brain dynamics? You will notice in the example, that I started the exchange with a well-phrasedquestion “What do you think will happen if your children could spend more time with dad?” The kind of question you ask makes a difference. When the parent is under stress, yes-no questions spark the Amygdala because they are perceived as oppositional, and fight or flight responses are more likely. However when you ask a question that cannot be answered reasonably by yes or no, the Hippocampus is energized to draw content for the reply, and the person is caused to reveal what is important to them based on the question. Yes-no reveals opposition. But content reveals the person. And now there is something to be heard. This second type of question is often referred to as open-ended. They invite participation in the discussion. They invite contribution. They invite collaboration in a problem-solving situation. And they reveal the person and what matters to them. Also note that a person’s response to these questions may initially reveal surface signsof something much more significant. When an open-ended question builds on its predecessor, the “peeling of the onion” effect can happen. As the person trusts the mediator to respect what is shared, the person can find even more important meaning to their struggle. For example, the mother in my example first responded to dad’s absence as her reason for her position. With further reflective questions, where she could hear her thoughts and feelings, she got down to the source – her experience of strain and fear. Compassion as a boundary Once compassion is discovered by the parties, it becomes a valuable boundary in their pursuit of answers. When a person is stressed, and self-focused, they have survival blinders on. They only consider ways that serve their own needs, be they basic or protective. The “box” of options for them is very small and increasingly restricted, the more stressed they are. But if a person can look at another with compassion, they will tend to put limits on looking solely at self benefiting ways and ways that cost the other person, so they can more effectively deal with a situation. Ironically, when a person finds they can experience compassion for the person they viewed earlier as a threat, they give themselves access to all the reality in the situation. Boundaries give us freedom! New possibilities emerge. When I first started mediation, I volunteered in small claims court. I remember a case where a dry cleaner had ruined a coat belonging to a very stylish woman. She brought the coat to the session. It was white wool with a brown suede collar; the brown color had bled into the white wool during the cleaning, destroying the appeal and appearance of the coat. The dry cleaner brought a book. He showed us the industry standards and the purpose of the tags required in garments to insure proper cleaning take place. We looked at the tag in the coat and compared it to the book. It only addressed the wool content, not the collar. He had done his job but she was still left with a damaged coat. She was an intelligent person and understood what happened. But her grief was apparent. I did not think this was all that could happen for these two good people. I tried to look beyond the situation and to find a question that could open a new direction. Remembering to be problem focused, I asked, “If the problem did not occur in the cleaning, where could it have occurred?” And we all took a moment to think about possibilities. Collectively we recognized that the manufacturer’s labeling was inadequate. Then the next questions was, “What means did we have to approach the manufacturer?” The woman noted that she had purchased the coat the local Air Force bases exchange where her husband was stationed. She saw this as an avenue of remedy. I asked the dry cleaner if he had any ideas? He offered to go with her to the base exchange and show the manager what he showed us. And the two left mediation as allies! That would not have been possible without the discovery of compassion. Years ago I discovered a bit of wisdom about life: the strength of one is less than one, the strength of two is more than two. Try it some time...try to move something by yourself. Then try it will a helper. It is surprising what the two can accomplish, in so many ways. Final thought Like for the children in the backyard, in mediation, compassion can be the “fence” around the parties’ world. It can paradoxically foster more creative approaches because there are now more degrees of freedom than when conflict separates people into isolated worlds. If compassion is to be fostered in a mediation setting, it has to begin with the mediator. It starts with the mediator’s sense of purpose in their vocation. The value of the mission statement helps the mediator foster, sustain, and return to this focus when lost. The way the mediator portrays the experience, the language used in the very first contact with a party, the dignity and acceptance conveyed by word and deed, the affirming of the worth of their lives as the purpose for the mediation, and a sense of hope for the future, all these things give the parties the quiet confidence to trust this critical moment in their life with this mediator. The spirit of compassion will become integrated into the sessions as the parties sit down at the table together. Subjectively experiencing both the mediator’s listening and modeling of listening, Trusting the possible revelations and discoveries. As the mediator asks questions, and reflects compassionately, the parties are also discovering themselves and what really matters to them. At the same time, the other person is given a chance to hear and respond to what really matters, not just the positions declared in a motion. Knowing that anger is a protective emotion gives the mediator the freedom to look for its source, for there is where the real concern, energy, and promise will be found. The mediator has influence that may seem mystical at times, especially in establishing the metaphors of the discussion. Seeking compassionate metaphors, the mediator helps the parties to risk opening their thoughts to more appreciative ways to recognize each other and the value of each of their roles in the situation. And finally, when the mediator promotes compassion as a boundary for the parties’ problem solving, they have opened new arenas of possibilities that avoid the polarities of conflict. The creativity comes from a “both-and” approach to solutions instead of the previous “either-or” that needed a higher power to judge. Boundaries give us freedom. Compassion, as a boundary, gives us redeeming creativity. I hope I have given you some food for thought about how you practice your mediation. I also hope I helped you see how what you do and say can bring a healing and life giving change to the clients you serve. Bibliography: Bob Bacic. “Compassion and Mediation.” Association for Conflict Resolution, Family Section teleseminar, 12/2/09, based on concept proposed by Evan Ash. Robert Benjamin. “Guerilla Mediation”. Mediate.com, 2004. Roger Fisher and William Ury. Getting to Yes. Penguin Books, New York, 1991. Roger Ley. “Compassionate or Benevolent Divorce.” Mediate.com. Rachel Naomi Remen. My Grandfather’s Blessings. Riverhead Books, New York, 2000. Marshall B. Rosenberg. Nonviolent Communication. Puddle Dancer Press, Del Mar, California, 1999.

Some people are good at negotiating in their own interest, and some people are not. Which one of these types of people do you want to be? One of your main jobs in life, one that will lead to increasing levels of self-confidence, is to become more effective in influencing others by learning great negotiation skills and choosing good questions to ask. In the many studies that have been done on effective negotiators, we find that they all have basically the same qualities and characteristics. Negotiation Skills are Learnable Contrary to popular belief, top negotiators are not hard bargainers and tough-minded personalities. They are not aggressive and pushy and demanding. They do not coerce their negotiating partners into unsatisfactory agreements. The best negotiators are invariably pleasant people. They are warm, friendly and low-keyed. They are likable and agreeable. They are the kind of people that you feel comfortable agreeing with. You have an almost automatic tendency to trust someone with great negotiation skills and to feel that what they are asking for is in the best interests of both parties. The Top 3 Negotiation Skills Skilled negotiators are usually quite concerned about finding a solution or an arrangement that is satisfactory to both parties. They look for what are called “win-win” situations, where both parties are happy with the results of the negotiation. In negotiating of any kind of contract, whether buying or selling anything, there are some basic negotiating skills that you need to learn in order to get the best deal for yourself and to feel happy about the results. 1) Choose Good Questions to Ask Good negotiators seem to ask a lot of questions and are very concerned about understanding exactly what it is you are trying to achieve from the negotiation. For example, in buying a house, both parties might start off arguing and disagreeing over the price. They begin with the position that the price is the most important thing and that is all that has to be negotiated. The skilled negotiator, however, will realize that price is only one part of the package. By using good negotiation skills, this negotiator will help both parties to see that the terms of the sale are also important, as are the furniture and fixtures that might be included in the transaction. Finding good questions to ask about a customer’s needs is the only way you will be able to find out in a negotiation what exactly is important to them and what benefits they are truly looking for. Price is not always the most important thing in a sale and it is important to show the customer other benefits they are receiving. 2) Patience Good negotiators are very patient. They concentrate first on getting agreement on all the parts of the contract that the two parties have in common before they go on seeking for amicable ways to settle the other issues. They also take the time to prepare good questions to ask to get clarity and understanding on each point as they go along, so that there is no confusion later. 3) Preparation is Key Preparation accounts for 90% of negotiating success. The more and better prepared you are prior to a negotiation, the more likely it is that the outcome of the negotiation will be satisfactory for all parties involved. Preparation requires you do two things. First get all the information that you can about the upcoming negotiation. Second, think the negotiation through carefully, from beginning to end, and be fully prepared for any eventuality. The first kind of information you need is about the product or service, and the person with whom you will be negotiating. You obtain this information by choosing good questions to ask that are well thought out. In this sense, information becomes a form of power, and the power is always on the side of the person with the best information. Take Action and Gain Self-Confidence! There is nothing that raises your self-confidence faster than to feel that you have been successful in negotiating a contract and that you have gotten a good deal as a result. And there is nothing that will lower your self-confidence faster than to think that you have been out-negotiated into a poor deal that you will have to live with. Therefore, negotiating skills are an important part of your personality development and of your sense of personal effectiveness and self-confidence. When you are a good negotiator, your self-confidence is higher and you feel more positive toward yourself and others in everything else that you do.

By Christopher Moore Summary written by Tanya Glaser, Conflict Research Consortium

What is Transformative Justice Transformative justice is a perspective that emerged from indigenous justice practices. It focuses on healing rather than revenge, and considers questions of justice and injustice in relation to both interpersonal and social-structural issues. Transformative justice is as concerned with the promotion of just processes as well as outcomes, and assumes that the two are inherently linked. A transformative approach views conflict as an opportunity to work with affected parties and communities to address underlying sources of harm, and to transform those conditions. It assumes that the people most affected by conflict should be directly involved in processes of resolution and justice, to the greater extent possible. Transformative justice recognizes the importance of accountability and responsibility, both for individuals and for organizations involved in justice work. It seeks non-exclusionary outcomes that maintain relationships between people and communities. Conflict An ongoing situation that is based on deep-seated differences of values, ideologies, and goals. The differences are hard to resolve because they reflect the core values of the disputants. The parties may not be influenced by facts and may not want to examine trade-off options. Conflict Management Conflict management generally involves taking action to keep a conflict from escalating further – it implies the ability to control the intensity of a conflict and its effects through negotiation, intervention, institutional mechanisms and other traditional diplomatic methods. It usually does not usually address the deep-rooted issues that many be at the cause of the conflict originally or attempt bring about a solution. Conflict Resolution Conflict resolution seeks to resolve the incompatibilities of interests and behaviours that constitute the conflict by recognizing and addressing the underlying issues, finding a mutually acceptable process and establishing relatively harmonious relationships and outcomes. Conflict Transformation Conflict transformation aims at shifting how individuals and communities perceive and accommodate their differences, away from adversarial (win-lose) approaches toward collaborative (win-win) problem-solving. Transforming a conflict is long-term process that engages a society on multiple levels to develop the knowledge, understanding and skills that empower people to coexist peacefully. Overcoming fear and distrust, dealing with stereotypes and perceptions, and learning how to communicate effectively are important steps in redefining relationships to bring forth social justice and equality for parties in conflict.

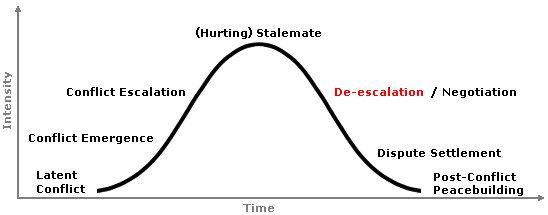

All conflicts, even intractable ones, eventually wind down and are to some degree transformed, so that they become regarded as tractable. Collective identities do change, sometimes abruptly, when state borders change or when states break up or even dissolve, as did the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia at the end of the twentieth century. Even without border changes, the content of a collective identity can and does change in the course of large-scale conflict. For example, the meaning of being South African changed as the wrongness of apartheid became a matter of wide consensus among all peoples of South Africa. Adversaries may come to recognize shared identities, sometimes induced by threats from a common enemy. Conflict de-escalation and transformation are often also associated with reduced grievances, at least for members of one side. This change occurs as relations between the adversaries change, in the course of the struggle. Thus, some rights that one party sought may be at least partially won, and that party's goals are then accordingly softened. Goals also change as they come to be regarded as unattainable or as requiring unacceptable burdens. Goals may then be recast so that they may be achieved with reasonable means. They may even be recast so as to provide mutual benefits for the opposing sides. For example, Frederik Willem de Klerk, as president of South Africa, led in reformulating the goals of the National Party, Afrikaners, and whites of South Africa to create a new, post-apartheid state. The methods that adversaries believe they can use effectively in a conflict do not become progressively more destructive as a conflict persists. As with goals, those methods, after a time, may become too costly or ineffective. Supporters may cease to be supportive, when norms are violated or costs become too burdensome. (This was certainly the case in the United States as the war in Vietnam wore on.) The methods may come to be seen as counterproductive for the goals sought, particularly if alternative methods, promising more constructive outcomes, seem feasible.